Series Overview

Grab your keyboard for the second deep dive of the series where we move from Power Automate to Visual Studio and get a look at the API that sits between your document libraries and Azure AI Search. As with the previous post there won’t be anything Foundry-specific here, but every bit is part of your agent's SharePoint curriculum. By leveraging a C# REST API, any architecture is poised to scale along with your organization as we all ascend AI mountain. Use the table of contents below in case you want to explore other posts in this series.

- Tradeoffs Between the Two Approaches

- SharePoint Knowledge Connections to Foundry Agents the Easy Way

- SharePoint Knowledge Connections to Foundry Agents the Hard Way

- Deep Dive 1: Extraction

- Deep Dive 2: Ingestion

- Deep Dive 3: Vectorization

- Azure AI Search Knowledge Connections to Foundry Agents

A Custom API to Sync SharePoint Content with Azure Storage

A link at the end of this post will take you to a GitHub repository with all the code that powers this API, so here we’ll focus more on functional endpoint logic than nonfunctional infrastructure plumbing. Unless you’re only here for some Azure AI Search code snippets, I recommend reviewing the previous two posts in this series to set the proper architectural context and explain any otherwise non sequitur mountain metaphors.

Let’s climb!

The API

Here is where most of the architecture’s customization comes in. As previously mentioned, my opinion is to keep Power Automate logic as simple as possible, only performing the tasks for which it is specialized. There are both Azure AI Search and Azure Storage activities available, but they are either in preview (as of November 2025) or don’t expose quite enough capabilities to achieve what I need. In terms of system telemetry, debuggability, and developer quality of life, I’d much rather live in Visual Studio with my fingers on the keyboard instead of “coding with my mouse” as it sometimes feels in Power Automate.

This API is a standard ASP.NET Core 10 Azure web app that uses the same Entra ID app for authentication as we saw in the previous post. At the endpoint level, the controllers are separated into two flavors: SharePoint data processing and Azure Search deployment. While the Azure resource group and all PaaS components are provisioned via Azure CLI (which is out of scope for this post), we need to use the Azure AI Search C# SDK to create the search topology (index, data source, etc.).

Being an absolute nut for automated deployments (and given how complex the search configuration is), I follow the same paradigm here as discussed in pervious posts: a preference to deploy this in C#. It just feels more robust and scalable verse trying to craft all the requisite JSON in PowerShell/Bash and needing cryptic string escaping or long chats with Copilot to get it right without the aid of a debugger. Then when the API inevitably evolves, it's much easier to deal with Nuget and compilation errors than having to hunt through stale JSON fragments.

This is the portion of the climb where we can start to see the mountain peak emerge from the wispy gray clouds. The two groups of endpoints shown below in the “A Little Swagger” section will take us to the summit, paying off a lot of the core ingestion logic for which SharePoint and Power Automate have already written the checks. But first we need to gear up for the final ascent with some details about the API implementation itself.

A Little Swagger (Optional Extra Credit)

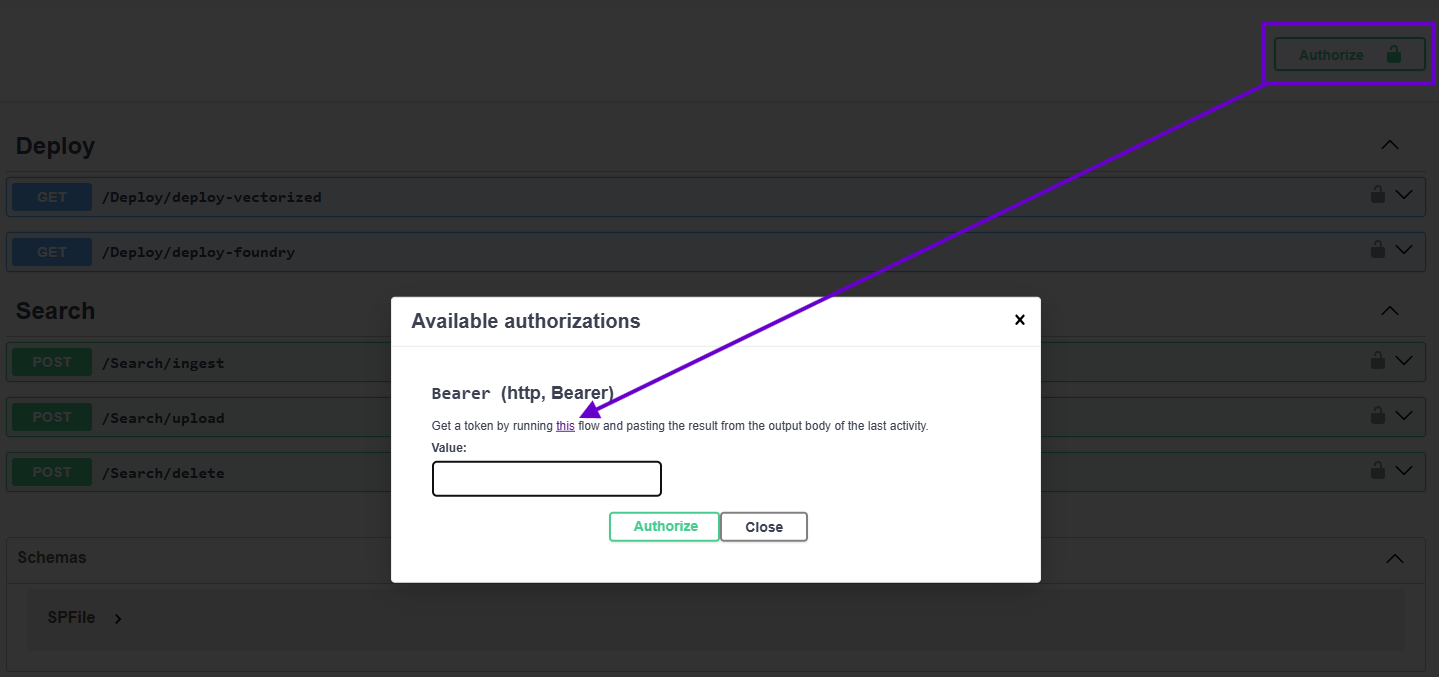

While there is nothing novel about using Swagger to put a face to your API’s endpoints, I do want to revisit something I mentioned in the “Token Acquisition” section of the previous post. When testing authentication via the Swagger UI, you have to manually copy/paste in your JWT authentication token when clicking the “Authenticate” button. Typically this entails something like logging into your SPA, pulling it out of the mess MSAL makes of your browser’s local storage, and then getting it into Swagger.

But since we have a flow designed to acquire a fresh auth token with no input parameters, can’t we just use that? Indeed! Let me share another bit from Program.cs where I put a link to Power Automate directly into the Swagger configuration code providing an easier way to authenticate the UI as a developer quality of life improvement. This is in the API's project's Program.cs file with the following Nuget packages installed:

1. . . .

2. builder.Services.AddEndpointsApiExplorer();

3. builder.Services.AddSwaggerGen(options =>

4. {

5. OpenApiSecurityScheme jwtSecurityScheme = new OpenApiSecurityScheme

6. {

7. In = ParameterLocation.Header,

8. Type = SecuritySchemeType.Http,

9. BearerFormat = FSPKConstants.Security.JWT,

10. Name = FSPKConstants.Security.Authorization,

11. Scheme = JwtBearerDefaults.AuthenticationScheme,

12. Description = string.Format(FSPKConstants.Security.TokenLinkFormat, builder.Configuration[FSPKConstants.Settings.TokenFlowURL])

13. };

14. options.AddSecurityDefinition(JwtBearerDefaults.AuthenticationScheme, jwtSecurityScheme);

15. options.AddSecurityRequirement(document => new OpenApiSecurityRequirement()

16. {

17. [new OpenApiSecuritySchemeReference(JwtBearerDefaults.AuthenticationScheme, document)] = []

18. });

19. });

20. . . .

With FSPKConstants.Security.TokenLinkFormat on Line #12 having a markdown string value of "Get a token by running [this]({0}) flow and pasting the result from the output body of the last activity." and the FSPKConstants.Settings.TokenFlowURL entry in appsettings.json being bound from…

1. {

2. . . .

3. "TokenFlowURL": "https://make.powerautomate.com/environments/<Power Platform environment id>/flows/<flow id>/details"

4. . . .

5. }

…we get the following when F5-ing the API project in Visual Studio (assuming you set "launchUrl" to "swagger" in launchSettings.json):

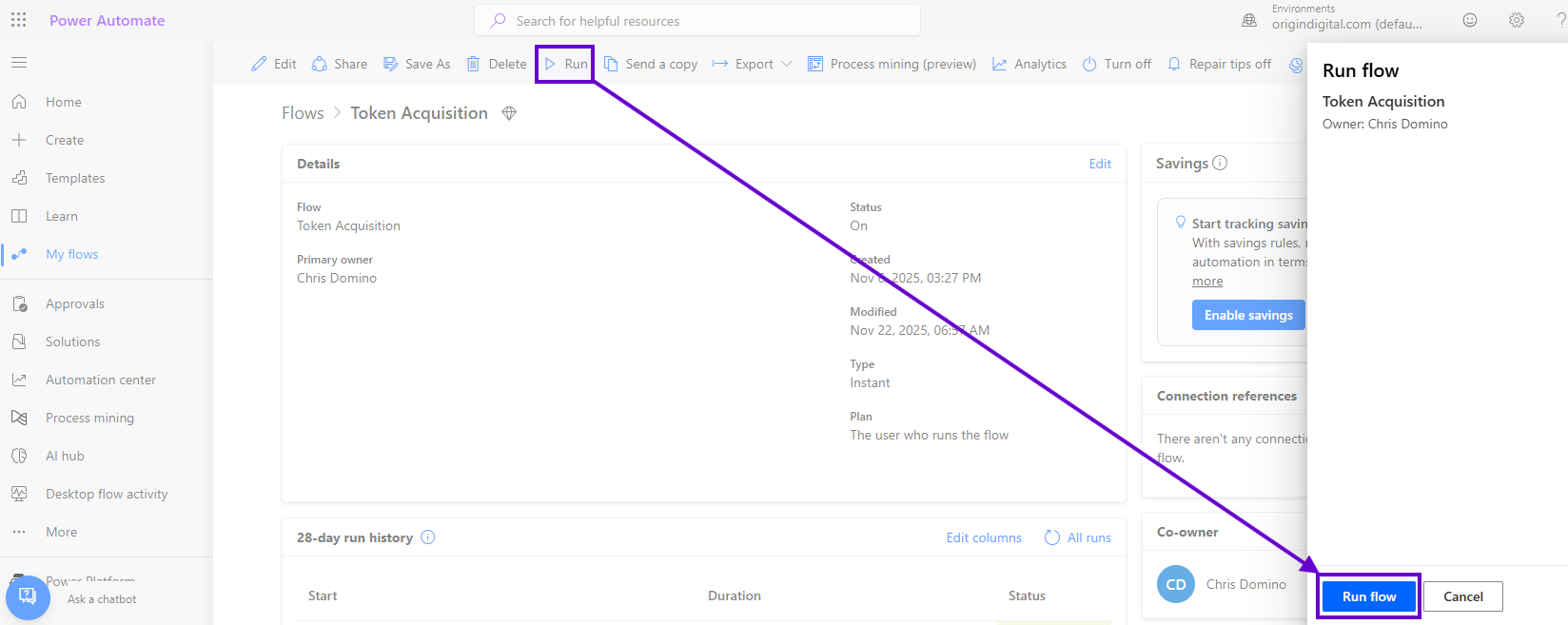

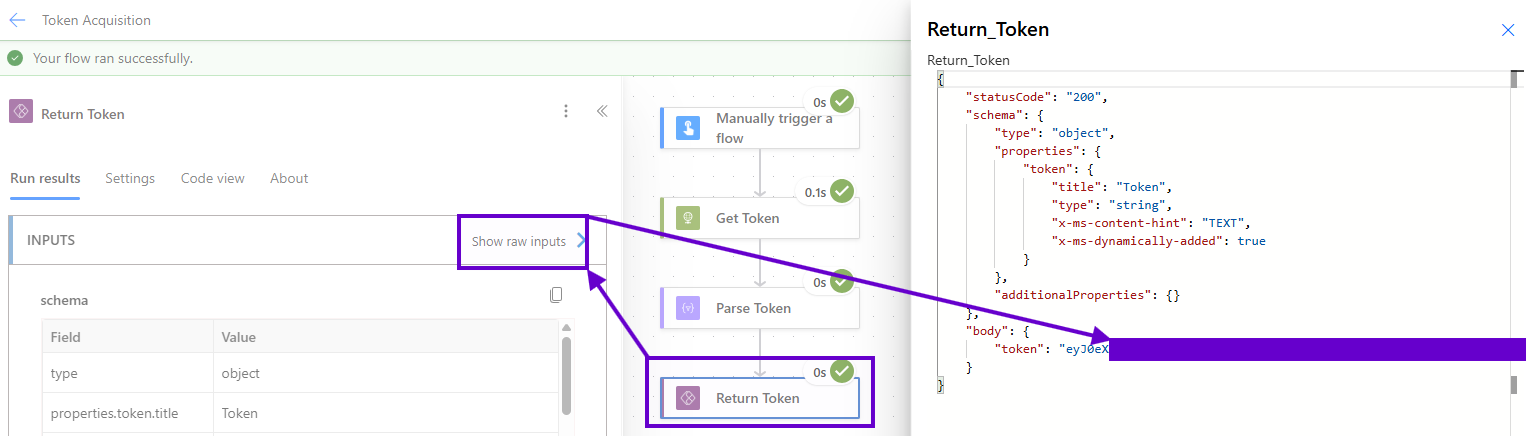

The link (above) sends the developer to Power Automate (below) in a new tab where, assuming they have access to the flow, they can click “Run” to get started.

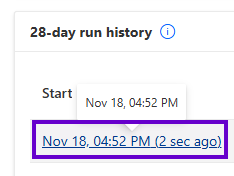

Next, after clicking “Run flow” in the drawer and then “Okay” when Power Automate confirms a successful execution (which only takes a second or two to run), click on the top row in the “28-day run history” section…

…and grab the token from the “Show raw Inputs” of the final activity:

Don’t worry: this process is much faster to execute than it is to read in a blog post! If this is still too many clicks for your workstream, you can enhance things further, for example, by adding an optional email address parameter as text input to the flow and use a Teams connector to IM yourself the token if the foresaid address is set.

Search Deployment

Using the Azure AI Search C# API to deploy the topology of an index, indexer, data source, and skillset is simply a lot of code; too much for what will be another beefy post. So first I will run through the skeleton logic and order of operations of the method that provisions the search components idempotently and then tell you the full story in the next installment of this series.

The code samples below are from a C# service that is called from the API’s “Deploy” controller. _searchIndexClient and _searchIndexerClient are both dependency-injected back in Program.cs with the Azure AI Search instance’s admin key pulled from Azure Key Vault. _searchSettings and _founderySettings, like entraIDSettings from the “Security” section of the third post in this series, are populated and singleton-ed in the same manner. (Note that while the Azure Key Vault code is out of scope for this series, the read me in the accompanying GitHub repository lists out the secrets that you’ll need.)

1) Delete the index by name if it exists.

1. await this._searchIndexClient.DeleteIndexAsync(indexName);

2) Create the SearchIndex object with a new VectorSearch property.

1. SearchIndex index = new SearchIndex(indexName);

2. index.VectorSearch = new VectorSearch();

3) Configure the index’s Similarity and SemanticSearch properties.

1. index.Similarity = new BM25Similarity();

2. index.SemanticSearch = new SemanticSearch();

3. index.SemanticSearch.Configurations.Add(. . .);

4) Configure the index’s cosine HnswAlgorithmConfiguration.

1. index.VectorSearch.Algorithms.Add(new HnswAlgorithmConfiguration(. . .));

5) Add an AzureOpenAIVectorizer that points to your Foundry instance.

1. index.VectorSearch.Vectorizers.Add(new AzureOpenAIVectorizer("sharepoint-foundry-vectorizer")

2. {

3. Parameters = new AzureOpenAIVectorizerParameters()

4. {

5. ApiKey = this._foundrySettings.AccountKey,

6. DeploymentName = this._foundrySettings.EmbeddingModel,

7. ResourceUri = new Uri(this._foundrySettings.OpenAIEndpoint),

8. ModelName = new AzureOpenAIModelName(this._foundrySettings.EmbeddingModel)

9. }

10. });

6) Add a VectorSearchProfile.

1. index.VectorSearch.Profiles.Add(new VectorSearchProfile(. . .));

7) Add “standard” SearchField objects for document chunking and each piece of SharePoint meta you wish to include in the index. Below is an example of the “URL” and “ChunkId” properties getting a LexicalAnalyzerName.Keyword keyword analyzer as both fields are used as unique identifiers (the URL for retrieval and the ChunkId as the required “key” property).

1. this.AddStandardField(index, "URL", false, true, false, false, true, LexicalAnalyzerName.Keyword, SearchFieldDataType.String);

2. this.AddStandardField(index, "ChunkId", true, false, true, false, true,LexicalAnalyzerName.Keyword, SearchFieldDataType.String);

3. . . .

4. private void AddStandardField(SearchIndex index, string name, bool isKey, bool isFilterable, bool isSortable, bool isFacetable, bool? isSearchable, LexicalAnalyzerName? analyzerName, SearchFieldDataType dataType)

5. {

6. . . .

7. }

8) Add a vector search field. We explicitly set IsHidden to false on Line #4 below; inspecting the decompiled Azure.Search.Documents.SearchField source code, this essentially forces IsRetrievable to be true (as required for vector fields) since this property isn’t settable in the Azure AI Search SDK.

1. index.Fields.Add(new SearchField(name, SearchFieldDataType.Collection(SearchFieldDataType.Single))

2. {

3. IsHidden = false,

4. IsSearchable = true,

5. VectorSearchDimensions = dimensions,

6. VectorSearchProfileName = profileName

7. });

9) Create the index.

1. Response<SearchIndex> indexResult = await this._searchIndexClient.CreateIndexAsync(index);

10) Delete the indexer by name if it exists.

1. await this._searchIndexerClient.DeleteIndexerAsync(index.Name);

11) Delete the data source by name if it exists.

1. await this._searchIndexerClient.DeleteDataSourceConnectionAsync("sharepoint-foundry-datasource");

12) Create a SearchIndexerDataSourceConnection against the Azure Storage blob container and save it. We are using the “Resource Id” of the storage account, which is the full “Azure path” as follows:

/resource/subscriptions/<subscription id>/resourceGroups/<resource group name>/providers/Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts/<storage account name>

The Azure AI Search instance is deployed with a managed identity that is granted the “Storage Blob Data Reader” role in the Azure Storage account. This allows us to use the resource id instead of a connection string for tighter security. Line #2 below enables automatic blob change tracking.

1. SearchIndexerDataSourceConnectiondataSourceConnection = new SearchIndexerDataSourceConnection("sharepoint-foundry-datasource", SearchIndexerDataSourceType.AzureBlob, this._searchSettings.AzureStorageResourceId, new SearchIndexerDataContainer("sharepoint-ingestion"));

2. dataSourceConnection.DataChangeDetectionPolicy = new HighWaterMarkChangeDetectionPolicy("metadata_storage_last_modified");

3. Response<SearchIndexerDataSourceConnection> datasourceResult = await this._searchIndexerClient.CreateDataSourceConnectionAsync(dataSourceConnection);

13) Delete the skillset by name if it exists.

1. await this._searchIndexerClient.DeleteSkillsetAsync("sharepoint-foundry-skillset");

14) Create a SearchIndexerSkillset with a SplitSkill and AzureOpenAIEmbeddingSkill. This is where all the chunking (split skill) and vectorization (AI skill) configuration happens to allow Foundry to reason over SharePoint data. If you need to tune up your agent’s responses based on the nature of the document library’s content, you’ll most likely do that here by updating the skillset’s properties. The next post in this series will detail out the individual skills.

1. Response<SearchIndexerSkillset> skillsetResult = await this._searchIndexerClient.CreateSkillsetAsync(skillset);

15) Create a SearchIndexer object.

1. SearchIndexer indexer = new SearchIndexer(index.Name, dataSourceConnection.Name, index.Name)

2. {

3. SkillsetName = skillset.Name,

4. Schedule = new IndexingSchedule(TimeSpan.FromMinutes(5))

5. };

16) Configure the indexer’s FieldMappings and Parameters properties.

1. indexer.FieldMappings.Add(new FieldMapping(. . .));

2. indexer.Parameters = new IndexingParameters() { . . . };

17) Create the indexer. Note that it will run immediately after provisioning completes.

1. Response<SearchIndexer> indexerResult = await this._searchIndexerClient.CreateIndexerAsync(indexer);

Hopefully that’s enough snippetry to understand the search topology provisioning of all the components needed to index, chunk, and vectorize content from an Azure Storage account. This order of operations is designed to be idempotent so that you can run it against any state your Azure AI Search instance might find itself in, especially after partial deployment errors encountered while getting this up and running the first time.

As previously mentioned, the GitHub repo below will have all the code that fills in the otherwise innocent-looking ellipses above. The source is verbose, with a lot of try/catch blocks and error handling logic since the Azure AI Search SDK will throw in certain scenarios were a null result would be expected (such querying for not-yet-existent indexes or indexers by name). Finally, the next post will focus entirely on the Azure AI Search schema with more samples that detail how the skillset cooks this data into robot food for your Foundry agents.

Document Processing

Let’s look at the other side of the wire that handles requests from the “Foundry Ingestion” and “Foundry Deletion” Power Automate HTTP calls. First off, to speed up testing after ensuring the token authentication was working, I added this to the base controller as a developer quality of life improvement:

1. #if DEBUG

2. [AllowAnonymous()]

3. #else

4. [Authorize()]

5. #endif

6. [ApiController()]

7. [Route("[controller]")]

8. public abstract class BaseController<T> : ControllerBase where T : BaseController<T>

9. {

10. protected readonly ILogger<T> _logger;

11. . . .

12. }

Next, we model the file payload using a class named in homage of an object from the old Microsoft.SharePoint server API:

1. public class SPFile

2. {

3. public string URL { get; set; }

4. public string Title { get; set; }

5. public string Name { get; set; }

6. public string ItemId { get; set; }

7. public string DriveId { get; set; }

8. public override string ToString()

9. {

10. return this.URL;

11. }

12. }

We will also need the “chunked” version of this file as it will represent the strongly-typed “document” of each record in the Azure AI Search index (again, the next post will detail the full field schema):

1. public class VectorizedChunk

2. {

3. public string URL { get; set; }

4. public string Title { get; set; }

5. public string Chunk { get; set; }

6. public string ChunkId { get; set; }

7. public string ParentId { get; set; }

8. public double[] TextVector { get; set; }

9. public override string ToString()

10. {

11. return this.URL;

12. }

13. }

Most Privileged Ingestion

As discussed in Part 3’s “Entra” section, The Hard Way’s "easy way" to talk to Microsoft Graph requires an app registration anointed with the Files.Read.All API permission. When a piece of code having the corresponding client secret is so blessed, it can access any file in the tenant. In this scenario, it only needs the drive and item ids of anything in OneDrive (as provided by the Power Automate flow in the previous post) for downloads. See the next section for, well, the hard way with much tighter security.

The following document processing code samples will exclude try/catch constructs, comments, regions, logging, etc. to keep things clean. First, we use Graph to get a byte array of the file that initially triggered the “Foundry Ingestion” flow which called this endpoint. The _graphClient is authenticated using a ClientSecretCredential in Program.cs with the same Entra ID app id / client secret leveraged in the Power Automate HTTP activities.

1. public async Task<byte[]> GetFileContentsMostPrivilegedAsync (SPFile file)

2. {

3. using (Stream contentStream = await this._graphClient.Drives[file.DriveId].Items[file.ItemId].Content.GetAsync())

4. {

5. using (MemoryStream memoryStream = new MemoryStream())

6. {

7. await contentStream.CopyToAsync(memoryStream);

8. return memoryStream.ToArray();

9. }

10. }

11. }

The main reason we do this ingestion logic via code is the next bit where we decorate an Azure Storage blob with metadata that the Azure AI Search indexer will gobble up. This is required because unlike Azure Table entities, blobs don’t have extensible strongly-typed properties. The details of the Azure Storage API usage is outside the scope of this post, but I do want to note that the _blobClient object is dependency-injected with the storage account connection string.

1. public async Task<bool> UploadFileAsync(SPFile file)

2. {

3. byte[] fileContents = await this._foundryService.GetFileContentsMostPrivilegedAsync(file);

4. BlobContainerClient container = this._blobClient.GetBlobContainerClient("sharepoint-ingestion");

5. BlobClient blob = container.GetBlobClient(file.Name);

6. Dictionary<string, string> metadata = new Dictionary<string, string>()

7. {

8. { nameof(file.Title), file.Title },

9. { nameof(file.ItemId), file.ItemId},

10. { nameof(file.DriveId), file.DriveId },

11. { nameof(file.URL), this.NormalizeURL(file.URL) }

12. };

13. string contentType = "application/octet-stream";

14. switch (Path.GetExtension(file.Name).ToLowerInvariant())

15. {

16. . . .

17. }

18. await container.CreateIfNotExistsAsync();

19. Response<BlobContentInfo> blobResult = await blob.UploadAsync(new MemoryStream(fileContents), new BlobHttpHeaders() { ContentType = contentType }, metadata);

20. . . .

21. return true;

22. }

Line #3 above is the call to the preceding code sample to get the file’s content from Microsoft Graph. Next, Line #’s 6-12 create the foresaid metadata for the blob. The omitted bits on Line #16 simply attempt to convert the file’s extension to a well-known content type for Office documents, PDFs, JSON, etc., falling back to the default application/octet-stream if not otherwise matched.

The NormalizeURL method called on Line #11 is of note because there is a bit of inherit risk around using a URL as a string-based unique identifier. I think it’s okay in this case because it’s only needed for file deletion clean up verses something more mission critical like fulfilling a user request with the URL as an input parameter.

1. private string NormalizeURL(string url)

2. {

3. return url.Trim().ToLowerInvariant();

4. }

A snag I ran into with Power Automate’s SharePoint trigger metadata is that it hands you an only partially encoded URL to the file in the “{Link}” raw output property; spaces are converted to “%20” but slashes and colons remain in plain text. Therefore, NormalizeURL simply trims and lower cases the string. Keep this in mind for the “Deletion” section below...

Least Privileged Ingestion

If Files.Read.All is too large a pill for your security team to swallow – as it probably should be – there is another way! Since no good deed goes unauthorized, we need to ensure that this API can only acquire data from SharePoint site collections explicitly allowed to make their files available to it. Part 3 of this series detailed out the configuration for this approach and the PowerShell to make it happen; here we will grab our Sites.Selected permission and get to work ingesting content following the principle of least privileges.

First, returning to the API project’s Program.cs, let’s take a look at the helper method that not only registers the GraphServiceClient for both levels of privilege, but also adds an HttpClient to the service provider. In this secure case, it's needed to specifically work around a nuance in Microsoft Graph’s C# API that will be discussd later:

1. private static void AddGraphClient(WebApplicationBuilder builder, EntraIDSettings entraIDSettings)

2. {

3. string[] scopes = ["https://graph.microsoft.com/.default"];

4. ClientSecretCredential clientSecretCredential = new ClientSecretCredential(entraIDSettings.TenantId.ToString(), entraIDSettings.ClientId.ToString(), entraIDSettings.ClientSecret);

5. builder.Services.AddHttpClient("SharePoint", client =>

6. {

7. AccessToken token = clientSecretCredential.GetToken(new TokenRequestContext(scopes));

8. client.DefaultRequestHeaders.Authorization = new AuthenticationHeaderValue(token.TokenType, token.Token);

9. });

10. builder.Services.AddSingleton(new GraphServiceClient(clientSecretCredential, scopes));

11. }

Line #5 is an example of allowing your services to demand an IHttpClientFactory implementation so that they can create named HttpClient instances the right way. In addition to handling their tricky disposal patterns properly and automatically, we can refactor a lot of boilerplate configuration code in one place: here in application startup where it belongs.

For instance, Line #7 leverages the synchronous version of the ClientSecretCredential’s GetToken method to avoid a race condition between the underlying asynchronous HTTP call and the code in this delegate (which fires with every request issued). This is something not normally needed, and therefore would be problematic to sprinkle around the codebase. Furthermore, with this pattern, we don’t have to expose the credential object – or worse – the token itself to our dependency injection; only the top level IHttpClientFactory.

Finally, here is the least privileged version of the API calls needed to turn our SPFile metadata into a byte array (as with the other code samples, usings, comments, error checking, and logging are removed for clarity):

1. public async Task<byte[]> GetFileContentsLeastPrivilegedAsync(SPFile file)

2. {

3. Uri uri = new Uri(file.URL);

4. string[] uriParts = uri.LocalPath.Split('/', StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries);

5. string managedPath = uriParts[0];

6. string siteCollectionURL = uriParts[1];

7. string siteCollectionPath = $"{uri.Host}:/{managedPath}/{siteCollectionURL}";

8. Site site = await this._graphClient.Sites[siteCollectionPath].GetAsync();

9. Guid siteId = Guid.Parse(site.Id.Split(',')[1]);

10. HttpClient client = this._httpClientFactory.CreateClient("SharePoint");

11. using HttpResponseMessage response = await client.GetAsync(string.Format("https://graph.microsoft.com/v1.0/sites/{0}/drives/{1}/items/{2}/content", siteId, file.DriveId, file.ItemId));

13. response.EnsureSuccessStatusCode();

14. return await response.Content.ReadAsByteArrayAsync();

15. }

Your first question should rightfully be: more URL string manipulation? Since we only have Sites.Selected, we need to start at the site level instead of going directly to the drive. To that end, while Graph’s SharePoint endpoints can accept the tidy guid form of a site collection’s unique identifier, it is not provided by Power Automate’s document library triggers. Fortunately, we can use the site’s absolute path to get it; unfortunately, it’s a mess.

Therefore, Line #’s 3-7 dissect the input URL as elegantly as possible from https://<tenant>.sharepoint.com/<teams or sites>/<site-relative-url>/<document library>/<file> and build it back up into a “site path” as <tenant>.sharepoint.com:/<teams or sites>/<site-relative-url>. Don’t forget that colon!

This is then fed to Graph on Line #8 to get back the “site id” which is also a disaster in the form: <site-relative-url>,<site-collection-guid>,<root-web-guid> that further needs to be parsed on Line #9 to ultimately get the middle guid we need. At lot of this complication stems from Graph having to distinguish between a site collection and the root web object (another relic from the “Microsoft.SharePoint” days).

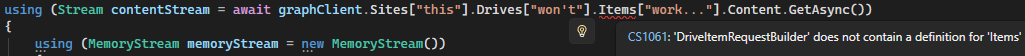

Next question: now that we are in “Graph code land,” why did we need that HttpClient to use the REST API? With Files.Read.All, and the drive and item ids from the flow, the most privileged approach can use Graph’s C# API in “OneDrive mode” to ostensibly yank a file from a folder in a single line. But in SharePoint’s corner of the SDK, while document libraries are indeed represented by drives, we can’t get to the Items collection (despite this library's otherwise high fidelity with the REST endpoints).

However, with a Graph-authenticated client, Line #’s 10-11 can perform a GET to acquire the byte array of the file directly. Finally, the same logic from the end of the “Most Privileged Ingestion” section then proceeds to upload it into Azure Storage. As you can see in the screenshot above, a site’s drive is more geared toward the object itself as an item (after all, everything stored in SharePoint is an item) instead of as a “virtual folder.”

And that’s it for the ingestion logic! Once the SharePoint file has become an Azure Storage blob, the Azure AI Search indexer will pick it up, chuck it up, and serve it up to our Foundry agent. We have now heaved ourselves to the summit after traversing the Hard Way up the mountain. However, we can’t just leave our equipment laying around littering the landscape; we need to clean up after ourselves…

Deletion

Finally, let’s take a spin through the deletion logic. This is like packing up our gear and anchoring a zipline to the peak of the mountain so we can repel down the other side when we're done. As previously mentioned, this probably could all happen in the Power Automate flow, but there turned out to be just enough tweaks and error checks required to again compel me to do this in of C# verses many complex workflow activities.

For the deletion method, I’ll leave some comments and error checking in place to elucidate key details without throwing too much code at you. Note that _searchClient is dependency-injected with the Azure AI Search instance’s admin key, following the same pattern as other Azure helper objects. Also, GetResponseErrorAsync is a utility method that takes in any Azure Response<T> object resulting from an API call and extracts a plain text string if an error is found within the raw response.

1. public async Task<bool> DeleteFileAsync(SPFile file)

2. {

3. BlobContainerClient container = this._blobClient.GetBlobContainerClient("sharepoint-ingestion");

4. BlobClient blob = container.GetBlobClient(file.Name);

5. await container.CreateIfNotExistsAsync();

6. Response<bool> deleteBlobResult = await blob.DeleteIfExistsAsync();

7. string deleteBlobError = await this.GetResponseErrorAsync<bool>(deleteBlobResult, ". . .");

8. if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(deleteBlobError))

9. throw new Exception($". . . {deleteBlobError} . . .");

10. if (deleteBlobResult.Value)

11. {

12. //create an exact match non-vectorized keyword query against the normalized url

13. string keyField = nameof(VectorizedChunk.ChunkId);

14. SearchOptions searchOptions = new SearchOptions()

15. {

16. VectorSearch = null,

17. SearchMode = SearchMode.All,

18. QueryType = SearchQueryType.Full,

19. Filter = $"{nameof(SPFile.URL)} eq '{this.NormalizeURL(file.URL).Replace(" ", "%20")}'"

20. };

21. //run query for documents keys with the given URL

22. searchOptions.Select.Add(keyField);

23. Response<SearchResults<VectorizedChunk>> searchResult = await this._searchClient.SearchAsync<VectorizedChunk>(null, searchOptions);

24. string searchError = await this.GetResponseErrorAsync<SearchResults<VectorizedChunk>>(searchResult, ". . .");

25. if (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(searchError))

26. throw new Exception($". . . {searchError} . . .");

27. //get document keys

28. List<string> documentsToDelete = new List<string>();

29. await foreach (SearchResult<VectorizedChunk> result in searchResult.Value.GetResultsAsync())

30. documentsToDelete.Add(result.Document.ChunkId);

31. //check documents (the search API will throw if the collection is empty)

32. if (!documentsToDelete.Any())

33. throw new Exception($". . . {file.URL} not found . . .");

34. //delete documents

35. Response<IndexDocumentsResult> deleteDocumentsResult = await this._searchClient.DeleteDocumentsAsync(keyField, documentsToDelete);

36. string deleteDocumentsError = await this.GetResponseErrorAsync<IndexDocumentsResult>(deleteDocumentsResult, ". . .");

37. . . .

38. return true;

39. }

40. else

41. {

42. . . .

43. return false;

44. }

45. }

Here we delete the blob representation of the SharePoint document from the Azure Storage container by name (Line #’s 3-9), and then query all chunks of the corresponding file from the search index by URL (Line #’s 12-33). The normalization issue is revisited on Line #19; the spaces need to be manually encoded since we have to reconstitute it by hand in the “Foundry Deletion” Power Automate flow using our plain-text environment variables due to the lack of available metadata in the SharePoint trigger.

I tried to do something more elegant with the URL like parsing it via WebUtility.UrlDecode and other similar out of the box options. But since the raw ingested link is only partially encoded, we start getting plus signs instead of %20 characters; manual string manipulation turned out to be cleanest option (for now; this is still keeping me up at night...).

To finish off the deletion, we build up a collection of document keys (“ChunkId” in this case) and then delete them all as a single batch on Line #34. And with this last piece of code, we have planted our Foundry flag on the summit of AI mountain and taken a well-deserved selfie atop the peak overlooking a vast vista of vectorized, agent-consumable SharePoint content.

You can find all code for this series here.

.svg)