Series Overview

One more deep dive to go! Now that we’ve seen the high-level Azure AI Search provisioning logic from the previous post, we will simultaneously take one step back to discuss the full search schema and two steps forward to explore the details of what puts “AI” into “Azure AI Search,” enabling it to be a Microsoft Foundry knowledgebase. Use the table of contents below incase you want to explore other posts in this series.

- Tradeoffs Between the Two Approaches

- SharePoint Knowledge Connections to Foundry Agents the Easy Way

- SharePoint Knowledge Connections to Foundry Agents the Hard Way

- Deep Dive 1: Extraction

- Deep Dive 2: Ingestion

- Deep Dive 3: Vectorization

- Azure AI Search Knowledge Connections to Foundry Agents

Configuring and Deploying Azure AI Search with C#

As mentioned in the second deep dive, C#-based Azure AI Search deployments are verbose and difficult to disseminate as narrative. There we went through the order of operations for provisioning search indexes, indexers, data sources, and skillsets as part of our custom API. Now let’s put search itself front and center and get into the AI weeds growing in this mountain pass as we make our way back down.

I will assume you have a basic knowledge of Azure AI Search architecture: indexers query data sources, map metadata, and store searchable records (referred to as “Documents” in the C# SDK) in database-table-like indexes using skillsets for transformations and AI data enrichment. However, I’ll try to provide as much detail as possible without this deep dive spiraling off the mountain. The sections below will break down all topological components and show the end results for each after an automated deployment.

Let’s climb!

Index

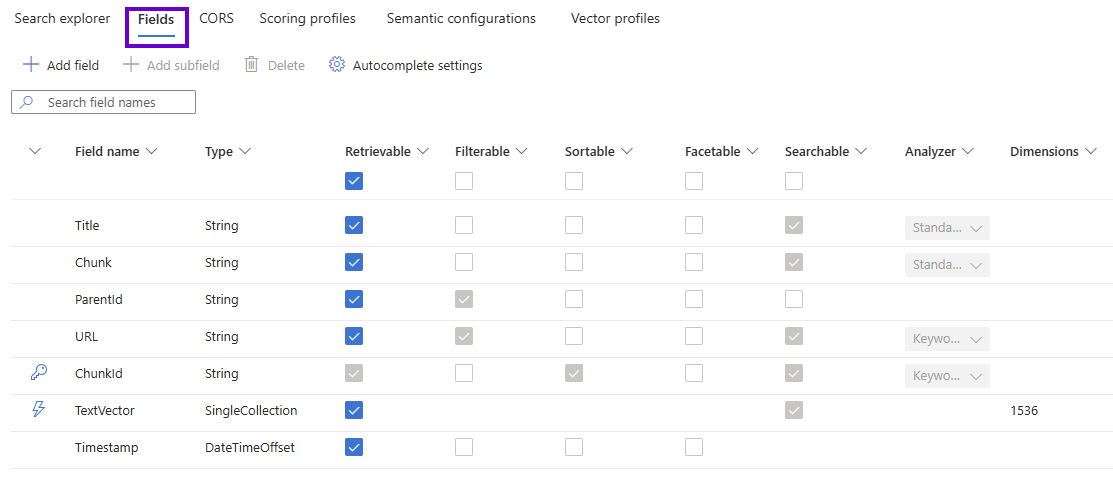

Let’s start with the search index. As with any architecture, everything is built upon a physical data layer. The schema below is the minimum required for agents to consume your SharePoint data. As we’ll see in the next post, you don’t have to map any fields in Foundry; Azure AI Search tools only need to be pointed at an index with this type of configuration for chat completions to work. If you’d like to get your hands on the raw JSON of any of these constructs, see the link at the end of this post.

The screenshots below are taken directly from the Azure Portal of my Azure AI Search instance. Another reason I prefer to idempotently deploy these components programmatically is because not everything is updatable via the UI; when it is, the editing experience is mainly limited to manual JSON updates in the browser.

Since this is error-prone and not repeatable across environments in an enterprise solution, automated provisioning is much safer. Given the fact that search data doesn’t have to be strictly durable (assuming you have the beathing room to wait for an indexer to rebuild its index during a production update), I prefer to just delete everything and redeploy during dev cycles to ensure I always have either a pristine search instance or an actionable error to debug.

In addition to the field names and data types, several intuitive flags define the nature of each column. Here are the full AddStandardField and AddVectorField methods introduced from the previous post. As mentioned there, setting IsHidden to false on Line #6 forces the read only IsRetrievable property to true which is almost always desired; the search engine can’t do much with a field it can’t see.

1. private void AddStandardField(SearchIndex index, string name, bool isKey, bool isFilterable, bool isSortable, bool isFacetable, bool? isSearchable, LexicalAnalyzerName? analyzerName, SearchFieldDataType dataType)

2. {

3. SearchField field = new SearchField(name, dataType)

4. {

5. IsKey = isKey,

6. IsHidden = false,

7. IsSortable = isSortable,

8. IsFilterable = isFilterable,

9. IsFacetable = isFacetable

10. };

11. field.IsStored = true;

12. field.IsSearchable = isSearchable;

13. field.AnalyzerName = analyzerName;

14. index.Fields.Add(field);

15. }

16. . . .

17. private void AddVectorField(SearchIndex index, string name, int dimensions, string profileName)

18. {

19. index.Fields.Add(new SearchField(name, SearchFieldDataType.Collection(SearchFieldDataType.Single))

20. {

21. IsHidden = false,

22. IsSearchable = true,

23. VectorSearchDimensions = dimensions,

24. VectorSearchProfileName = profileName

25. });

26. }

Analyzers are like skillsets that perform transformations against a particular field instead of the entire file. A built-in analyzer that makes strings more amenable to full text search queries by chunking them into tokens (not to be confused with AI jargon in this context) always runs by default. For our purposes, we leverage a keyword analyzer to not tokenize columns acting as unique identifiers so queries (such as what we issue in the “delete” endpoint from the second deep dive) can match documents against their full input URLs.

Here are the index’s field descriptions:

- Title: this holds the absolute URL to the blob in the Azure Storage container. As previously mentioned, the indexed file's title from SharePoint could be mapped to custom metadata and get vectorized as well.

- Chunk: a segment of plain text extracted from the source document.

- ParentId: a (very) long unique identifier; all chucks from a source document will have the same value (although there is no “parent” item in the index; this isn’t a hierarchy or search sub field).

- URL: the absolute URL to the file in SharePoint.

- ChunkID: an even longer unique identifier suffixed with the page number extracted from the source document for each chunk. This is the key field, distinct across the index.

- TextVector: the vector field as a numerical (float) array representation of the chunk in robot language. The dimensionality depends on the Foundry embedding model used (which is “text-embedding-3-small” for this post, having 1,536 dimensions).

- Timestamp: this holds the UTC (ISO 8601 formatted) date when the blob was last modified, which is automatically curated by the Azure Storage account for us. This is used for file change tracking.

This shows how Azure AI Search stores extracted document chunks. I have added in custom SharePoint and blob metadata via the “URL” and “Timestamp” fields above respectively. Just to reiterate an important point: the source file itself is not represented in the index under this architecture; only its unique chunked segments loosely associated with one another via matching values of their “ParentId” fields.

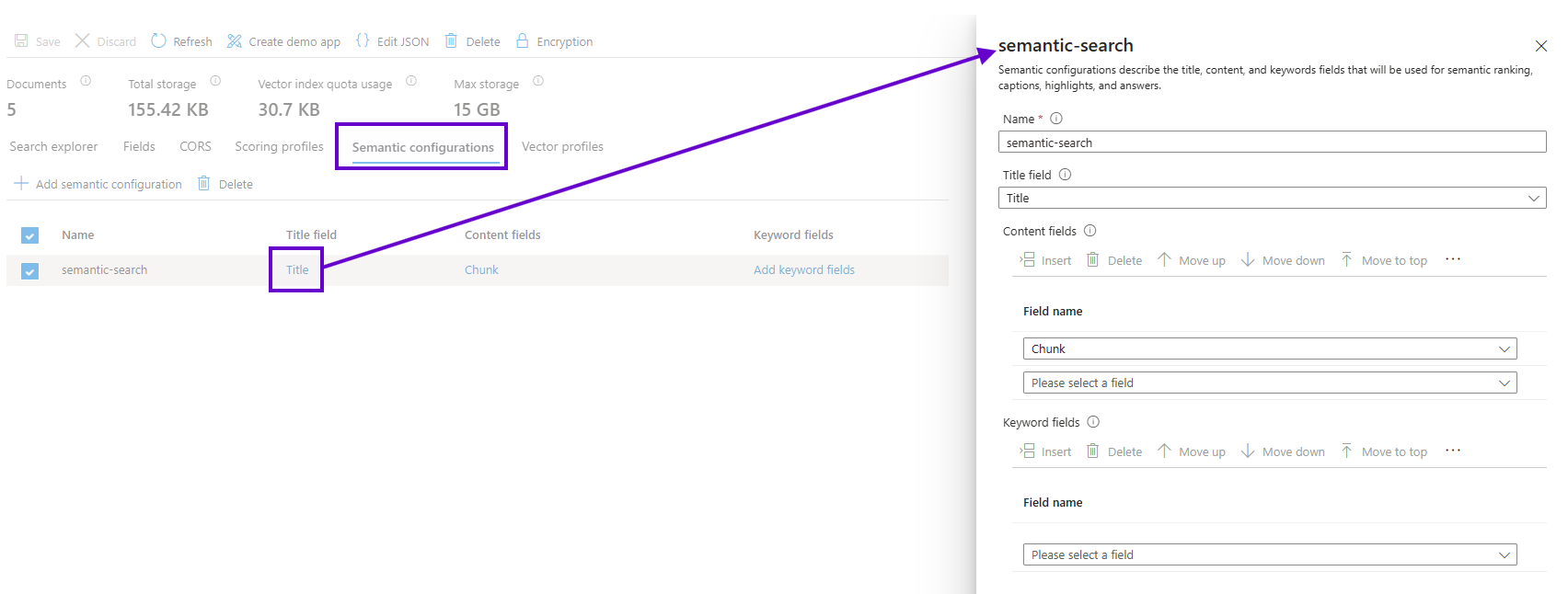

Let’s take a spin through the other tabs, where there’s not much to elucidate without getting too deep into the bowels of Azure AI Search configuration. Here is the semantic configuration, which identifies the “Title” and “Chunk” fields as the criteria for ranking result relevancy.

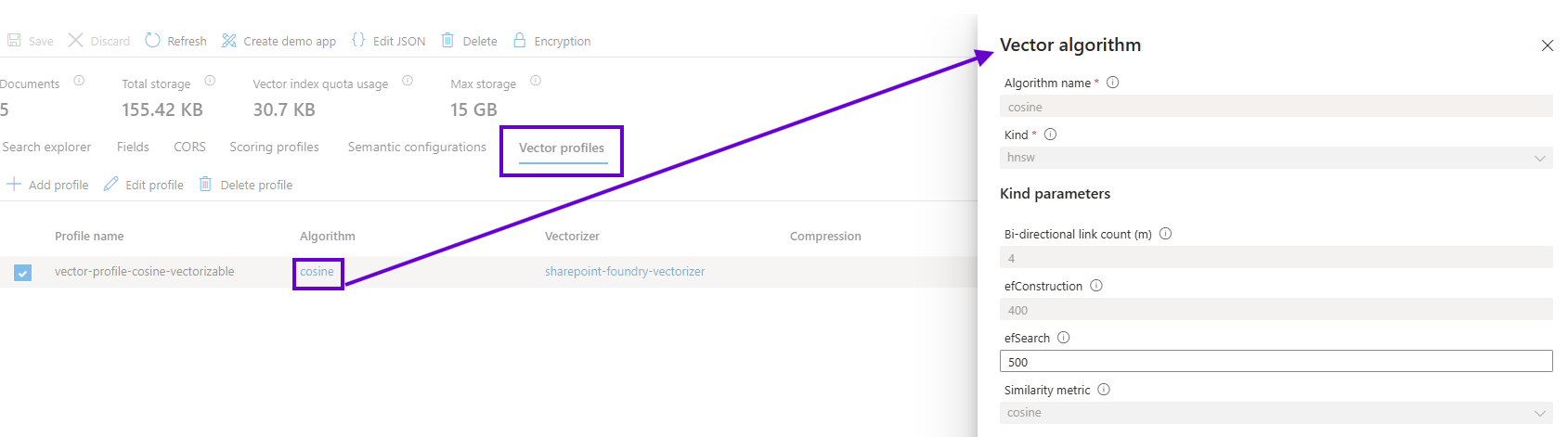

Next is the vector profile’s cosine similarity algorithm which specifies how the Foundry agent’s LLM will query high dimensional vector space. This is another knob on the Hard Way’s control panel that can be used to fine tune chat completions.

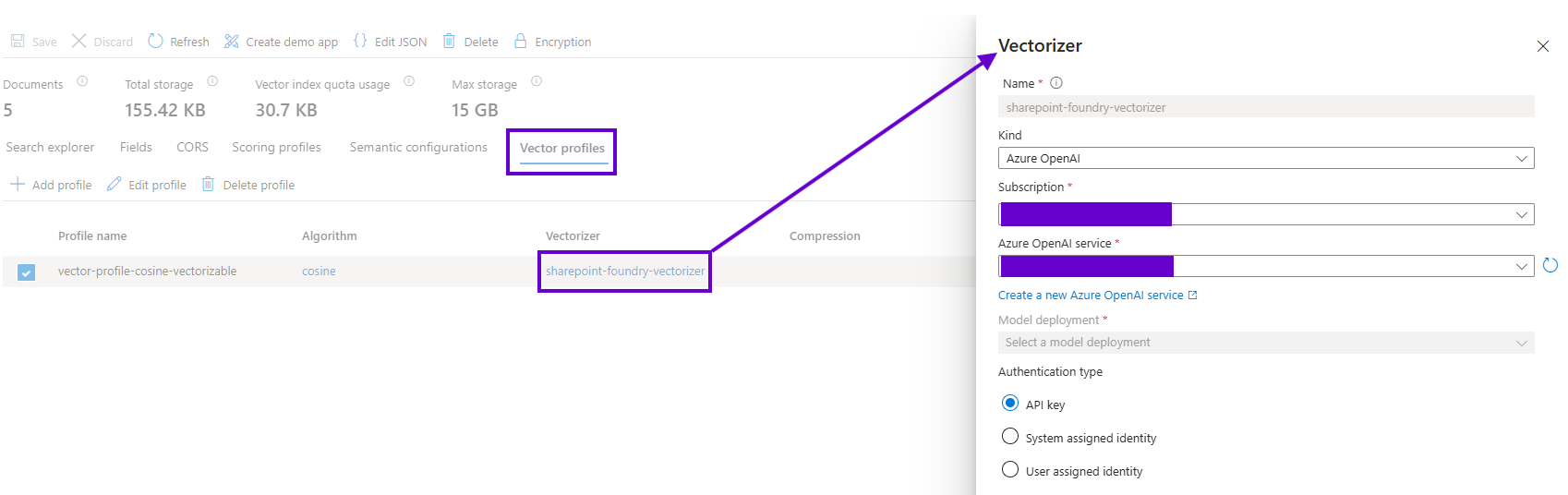

And finally here is the vectorizer which uses a Foundry OpenAI instance’s embedding model to translate plain text into the robot language of floating point arrays.

Another advantage of deploying search topology via code instead of configuring it from the UI is that I have observed the values in the “Azure OpenAI service” dropdown above not including Foundry OpenAI instances; only top-level PaaS Azure OpenAI resources deployed directly. However, using code to feed the vectorizer the correct connection information for an OpenAI instance umbrellaed under Foundry works just fine!

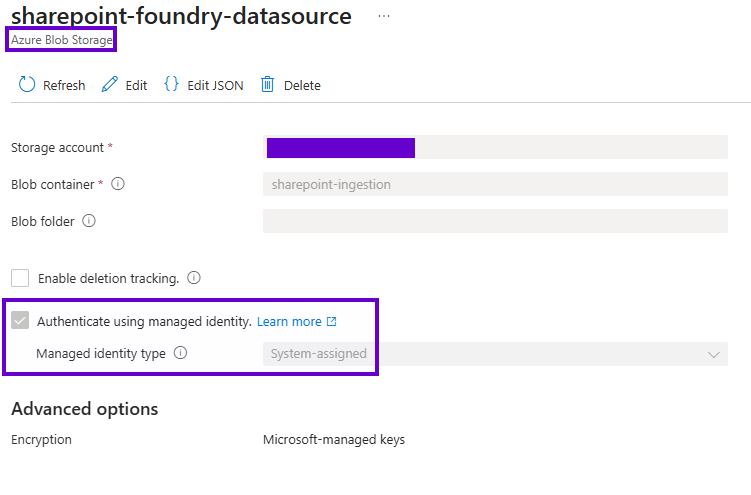

Data Source

The role of the data source is to simply define what, where, and how the indexer should run its queries. This is the simplest component in the topology, especially given the out of the box support for Azure Storage blob containers. The screenshot below shows the previously mentioned security enhancement of using managed identities with RBAC instead of exposing API keys or connection strings.

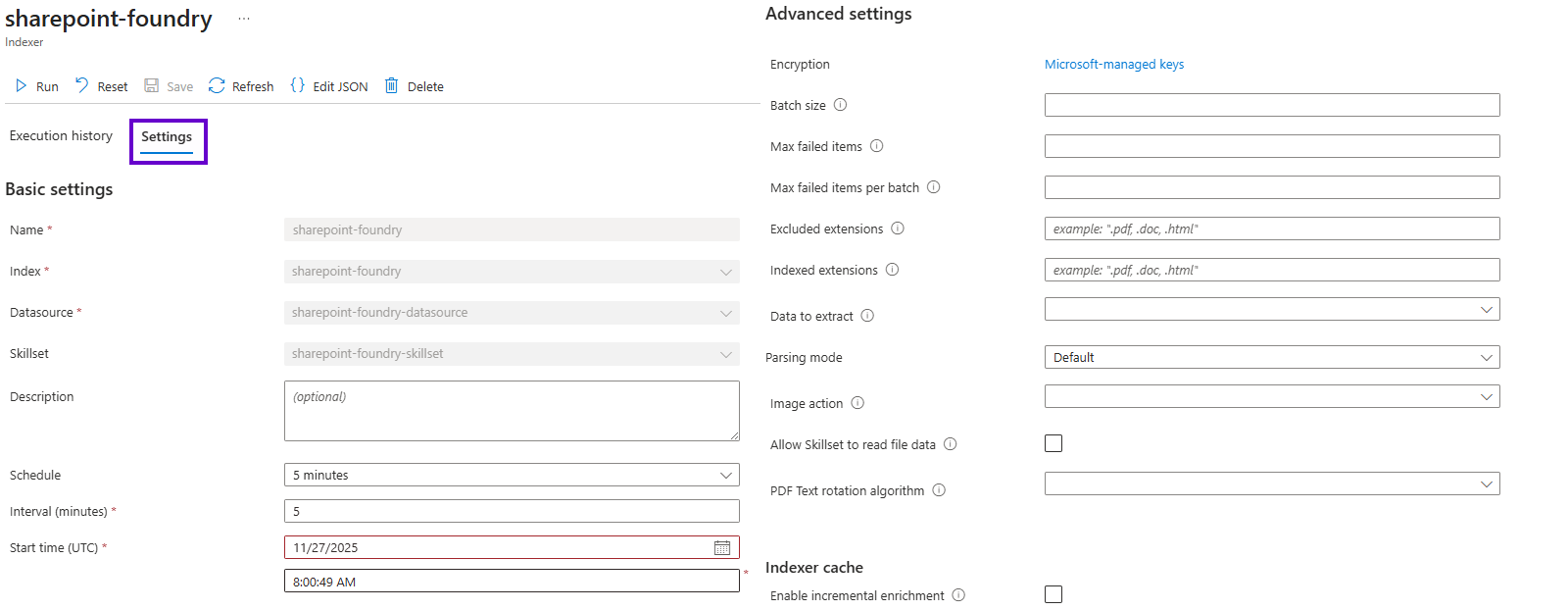

Indexer

The indexer is probably the least-customized component when configuring Azure AI Search for Foundry agents; what we do below is no different than if this instance was built to implement a “conventional” app’s search functionality. Beyond tweaking the scheduling (which doesn’t affect cost) of the indexer’s runs, the remaining configuration knobs are typically only adjusted for complex scenarios.

However, there is one important aspect of the search architecture that the indexer owns: mapping source file metadata to index fields. For more strongly-typed entity-based data sources (such as Azure Tables or SQL Server database views), the index fields will typically be designed to have the same names as the data source’s entity properties; the indexer can then map things automatically. The only time I’ve had to extend this is when my data source properties had names breaking index field conventions.

But since we are using blobs for robot food, there are only a few out of the box Azure Storage auditing properties available to include in the index. These use slightly cryptic internal names, so I like to map them to something more intuitive (for aesthetic reasons rather than functional) as follows:

- metadata_storage_path: Title

- metadata_storage_last_modified: Timestamp

The ensuing code is straightforward (constants removed for clarity):

1. indexer.FieldMappings.Add(new FieldMapping("metadata_storage_path")

2. {

3. TargetFieldName = "Title"

4. });

5. indexer.FieldMappings.Add(new FieldMapping("metadata_storage_last_modified")

6. {

7. TargetFieldName = "Timestamp"

8. });

To round out the logic, the indexer only additionally needs to know which index and data source (see Line #1 below; I typically use the same name for the indexer as the index) it’ll be working with, an optional skillset (Line #3), and a hint that it will be in the business of parsing blobs (Line #11). The code sample above resides on Line #6 here:

1. indexer = new SearchIndexer(index.Name, dataSourceConnection.Name, index.Name)

2. {

3. SkillsetName = skillset.Name,

4. Schedule = new IndexingSchedule(TimeSpan.FromMinutes(5))

5. };

6. . . .

7. indexer.Parameters = new IndexingParameters()

8. {

9. IndexingParametersConfiguration = new IndexingParametersConfiguration()

10. {

11. ParsingMode = BlobIndexerParsingMode.Default

12. }

13. };

Skills And Skillsets

I saved this for last since it is finally getting into the AI bits that allow a search index to be reasoned over by Foundry agents. This is what elevates Azure AI Search from mere natural language processing to full LLM-ready embedded vectorization – essentially the difference between generic search capabilities from the epochs before and after Azure OpenAI came into our lives.

A skillset is comprised of two things: a collection of individual skills for specific data transformations and a set of projections that tell the indexer how to parse a source file. Let’s tackle the individual skills first to set some context, and then see how they come together to perform the quintessential task of making your SharePoint content LLM-consumable.

Chunking

The first skill we saw in the previous post – text splitting – instructs the indexer how to chunk the blobs it finds in the Azure Storage container. The following code will yield the JSON shown beneath it. Note that unlike the other search components, skillsets don’t have any administrative UIs in the portal save the foresaid raw JSON editors.

1. SplitSkill splitSkill = new SplitSkill([new InputFieldMappingEntry("text")

2. {

3. Source = "/document/content"

4. }], [new OutputFieldMappingEntry("textItems")

5. {

6. TargetName = "pages"

7. }])

8. {

9. Name = "split-skill",

10. Context = "/document",

11. MaximumPagesToTake = 0,

12. PageOverlapLength = 500,

13. MaximumPageLength = 200,

14. TextSplitMode = TextSplitMode.Pages,

15. DefaultLanguageCode = SplitSkillLanguage.En

16. };

This skill splits the content by page and is told how many characters worth of size and overlap to use when determining the segmentation of the final indexed chunks. If your agent seems confused, try adjusting these values in the search topology deployment code so it can get better context windows.

In this sample, we see some input/output mappings that don’t resemble anything in our schema. Skillsets use abstractions of an incoming document to enrich it with additional attributes via an XPath-like language with specific identifiers that refer to the shape of a document instead of its metadata. Back in SharePoint, we care about a file’s data as bytes and its properties (such as Title, URL, etc.) as fields; the CMS rarely considers concepts such as text or pages explicitly.

But when feeding this content to an LLM, Azure AI Search needs to be able to first deconstruct a document logically into pages (as used in this example; sentences are also supported via the TextSplitMode on Line #14 above) before it can extract chunks as vectors. Each chunk is then an element of a virtual array within the generated “enrichment tree” of each file that can be mapped to a search field or other outputs. Again, the new concept we’ll be seeing in this section is search consuming abstractions over a file’s logical structure in addition to its physical properties.

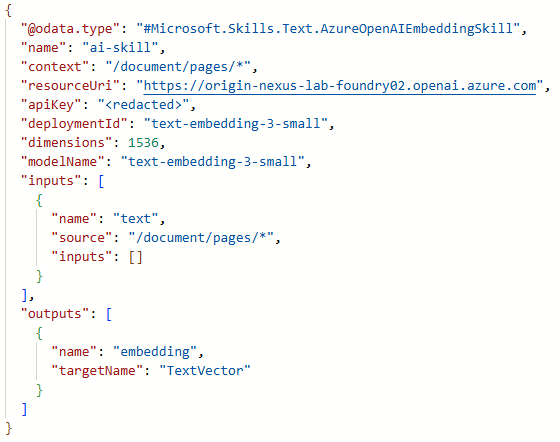

Vectorization

Next, the AI skill (which also needs Azure OpenAI connection information at deployment time) controls how the vectorization is performed so that each chunk can be translated into what I have affectionately been referring to as “robot language” for the LLM. If your Foundry deployments adopt a new embeddings model, this code will have to be adjusted.

1. AzureOpenAIEmbeddingSkill aiSkill = new AzureOpenAIEmbeddingSkill([new InputFieldMappingEntry("text")

2. {

3. Source = "/document/pages/*"

4. }], [new OutputFieldMappingEntry("embedding")

5. {

6. TargetName = "TextVector"

7. }])

8. {

9. Name = "ai-skill",

10. Dimensions = 1536,

11. Context = "/document/pages/*",

12. ApiKey = this._foundrySettings.AccountKey,

13. DeploymentName = this._foundrySettings.EmbeddingModel,

14. ResourceUri = new Uri(this._foundrySettings.OpenAIEndpoint),

15. ModelName = new AzureOpenAIModelName(this._foundrySettings.EmbeddingModel)

16. };

As you can see, this is basically throwing Azure Open AI at the logical plain text pages of the source file and catching the vectorization in the “TextVector” field using the embedding model from our Foundry instance. Again, understanding the abstraction of a document via its enrichment tree will help elucidate how this skill fillets content into robot food.

Projections

Beyond a JSON array of skills (which each screen shot above shows as an object element within it), the skillset itself has metadata that includes a definition of its “projections.” I’ve flirted with these metadata mappings in previous code samples, so let’s take a look at what is provisioned here.

The following code…

1. string allDocumentPages = "/document/pages/*";

2. SearchIndexerSkillset skillset = new SearchIndexerSkillset("sharepoint-foundry-skillset", new SearchIndexerSkill[] { splitSkill, aiSkill })

3. {

4. IndexProjection = new SearchIndexerIndexProjection(

5. [

6. new SearchIndexerIndexProjectionSelector(index.Name, "ParentId", allDocumentPages, new InputFieldMappingEntry[]

7. {

8. new InputFieldMappingEntry("ChunkId")

9. {

10. Source = allDocumentPages

11. },

12. new InputFieldMappingEntry("TextVector")

13. {

14. Source = $"{allDocumentPages}/TextVector"

15. },

16. new InputFieldMappingEntry("URL")

17. {

18. Source = "/document/URL"

19. },

20. new InputFieldMappingEntry("Title")

21. {

22. Source = "/document/Title"

23. },

24. new InputFieldMappingEntry("Timestamp")

25. {

26. Source = "/document/Timestamp"

27. }

28. }),

29. ])

30. {

31. Parameters = new SearchIndexerIndexProjectionsParameters()

32. {

33. ProjectionMode = IndexProjectionMode.SkipIndexingParentDocuments

34. }

35. }

36. };

…provisions a skillset shown in this JSON fragment:

The main paradigm is dissecting a source “parent” document into “child” chunks that become the physical searchable entities in the index. This is the “where” to the text split skill’s “how.” As previously mentioned, there is no need to index the source document itself for Foundry agents specifically, but the concept might be useful if you leverage this implementation for different apps. This is controlled by the “parameters” element (Line #33 above). As I mentioned previously, this configuration is not hierarchical as there is no actual parent document in the index.

Finally, we see that the projections come in two flavors under the “selectors” (another X-Path concept) element. The first two field mappings with “source” values starting with “/document/pages/*” are the chunk-specific properties unique to each segmentation of the raw file; it is how the foresaid “structural abstractions” are defined since they do not exist as explicit properties in SharePoint or Azure Storage.

The final three are meta-driven to allow us to map physical document properties down to fields on each indexed chunk. Note that the search SDK used in the topology deployment code will bomb if any of your custom metadata fields are not mapped here as projections, so just keep names consistent (constants help) and this should feel similar to the more out of the box indexer mappings we saw above.

Our descent down the other side of AI mountain is almost complete; the Microsoft Foundry destination where we realize all this work as an Azure AI Search tool allowing an agent to reason over SharePoint data is the last mile of our journey in the next and final post of this series. As I’ve repeated throughout the deep dives, search deployment code is dense and wrought with cryptic strings and several layers of mappings; the GitHub repository below should give you everything you need to find the trial if you lose your footing along the way.

You can find all code for this series here. In the root folder, you’ll also see the sample JSON files for each search component shown in the screenshots above:

- Index

- Indexer

- Data Source

- Skillset

.svg)